Many adults – many well-known authors in fact – re-read books that in childhood had a big impact. So why is children’s literature not considered worthy of major awards?

Stuart McQuarrie as Mr Snow and Ethan Hammer as Emil in the National Theatre production of Emil and the Detectives Photograph: Tristram Kenton/Tristram Kenton

SF Said Monday 16 February 2015 16.57 GMT

Who today remembers the plays of AA Milne or the political writing of Erich Kästner? Yet their children’s books are read the world over.

Salman Rushdie has suggested that of all his work – including Midnight’s Children, which won the Best of the Booker – his children’s books may last the longest. He recalled being urged to write them by publisher Kurt Maschler, who had published Kästner’s Emil and the Detectives.

“As Kurt Maschler said to me, ‘It’s the only one of his books that’s still in print!’ That was a lesson I didn’t forget. It may end up that Haroun and the Sea of Stories and Luka and the Fire of Life are the only books of mine that remain in print. And that would be fine, actually.”

Neil Gaiman tells the similar story of AA Milne, who is no longer remembered as a West End playwright or features editor of Punch, but only as “the author of two books of short stories and two books of verse for small children”.It’s striking how long children’s books can last. One explanation may be the way in which they’re read. They become part of our emotional autobiographies, acquiring associations and memories, more like music than prose.

Another explanation may lie in the fact that children’s books are designed with re-reading in mind. For all children’s writers are conscious that our books may be re-read by children themselves.

“Yes, kids read and re-read favourite books,” says Francesca Simon. “My favourite Horrid Henry books to sign are the ones which are so dog-eared and stained through re-reading they are practically translucent. When Simon Mayo interviewed me, he commented that he had read them to his kids over 200 times. He looked like a man undergoing penance …”

Enduringly odious … Horrid Henry: Tony Ross/Orion

Photograph: illustration©Tony Ross/PR

A similar view is taken by Gaiman, who writes for all ages. “When I’m writing for kids,” he says, “I’m always assuming that a story, if it is loved, is going to be re-read. So I try and be much more conscious of it than I am with adults, just in terms of word choices. I once said that while I could not justify every word in American Gods, I can justify every single word in Coraline.”

Many parents will know this already. They sometimes even fear there’s something wrong with a child who re-reads favourite books rather than new ones.

“There’s nothing wrong with them,” says Charlotte Hacking, of the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE). “Children need to read and re-read and keep coming back to books, looking at them in different ways. It’s actually a really good thing; it allows you to go deeper.”

So re-reading is a given for children’s authors. It’s one reason why we try to write books that have many layers and work on different levels, rewarding re-reading by growing richer each time.

But if this is true, then why are children’s books rarely considered for literary prizes such as the Man Booker and the Costa? This year’s Costa coverage barely considered the possibility that the children’s prize-winner, Kate Saunders’s Five Children on the Western Front, might win the overall prize.

Yet it’s an exceptional book that already feels like a classic. In a stunning twist on E Nesbit’s Five Children and It, Saunders takes those carefree Edwardian children and plunges them into the first world war. For they belonged to the generation who would die in the trenches, and she works this to devastating emotional effect.

“It’s an amazing book,” says Guardian children’s books editor Julia Eccleshare. “If that was an adult book working with Jane Austen, as it were, people would be wowing about it. The textual play on a classic, in the adult world, would receive far more praise than I think she has been noticed for – yet.”

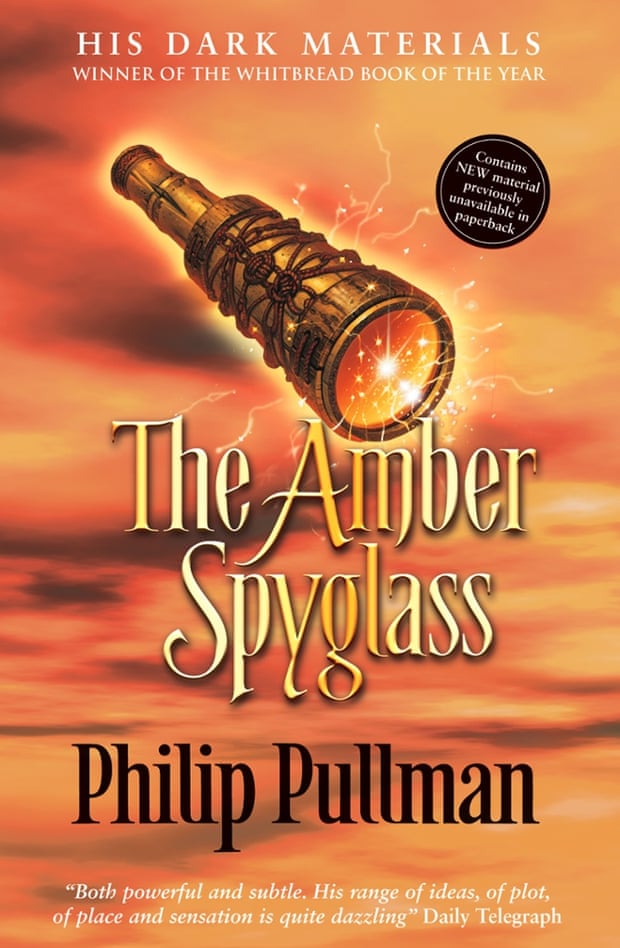

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, given that only one winner of the Costa/Whitbread children’s book prize has ever won the overall book of the year. That was Philip Pullman’s The Amber Spyglass, back in 2001.

The Amber Spyglass

Illustration: PR

“It hasn’t happened since,” says Pullman. “But one day they’ll have to find a book they just have to give it to. Maybe one day a children’s book will get the Booker prize. Why not? Why not a children’s author winning the Nobel prize?”

Sarah Churchwell, one of last year’s Booker judges, has written about the judging process. She said that it “asks of books something they’re not really designed for: to be read three times in a row by people probing for weakness. Most books just crumble under that kind of pressure: only the most rich, the most layered, continue to dazzle and reveal ever more.”

She concluded that only two books on last year’s list met this criterion. Yet as a children’s writer, I couldn’t help thinking that this is exactly what all children’s books are designed to do. They may achieve it to a greater or lesser degree, but that’s always the aim.

Children’s laureate Malorie Blackman agrees. “Call me biased,” she says, “but I find the standard of storytelling in children’s books and books for young adults second to none. I find it telling that even now, there are far more children’s books and books for teens that I’d like to re-read than books for adults.”

These are the books that get handed down through generations, becoming classics, but perhaps their readability works against them. Reflecting on the children’s books he still re-reads, Pullman observes: “Part of the joy of all these books is a sort of perfect lightness and grace in the words. Everything is in its right place. Not a comma needs changing. Things like that make it possible to read them again and again without fatigue.”

That lightness and grace is a hallmark of the best children’s writing, along with the multi-layered richness Churchwell found so rare. Yet only The Amber Spyglass and Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog In the Night-Time have ever appeared on a Booker longlist. Not one single children’s book has made the shortlist, let alone won, in the history of the prize.

Luke Treadaway as Christopher in The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Night-Time

Photograph: Tristram Kenton/Tristram Kenton

Meanwhile, media coverage of children’s books is vanishingly small. Former Children’s laureate Julia Donaldson has pointed out that they get less than one in 40 of all review spaces. And yet children’s books now account for one in four of all books sold in the UK. This is the most vibrant sector of British publishing, outperforming adult fiction in 2014.

A generational shift may now be occurring. For many of my generation, growing up in the 1970s with books like Watership Down, story is story, regardless of age. That’s even truer of younger writers.

“I certainly don’t see children’s books as being in any way lesser than adult literature,” says Katherine Woodfine, born in the 1980s, whose debut The Mystery of the Clockwork Sparrow is published this year. “If anything, I’d argue the opposite. Children’s books can have a hugely powerful effect on their readers, helping to shape and inform their view of the world, in a way that adult books rarely achieve. They’re the first literature we engage with, and what’s more, they’re often the first art works we ever encounter.”

Woodfine’s response to the lack of coverage is to create new media space. Together with Melissa Cox of Waterstones, she hosts Down the Rabbit Hole on Resonance 104.4FM: the only dedicated children’s books radio show. It’s part of a vibrant online community, too. Twitter, the Guardian children’s books site, and other digital spaces are connecting writers, readers, bloggers, vloggers, booksellers, librarians and teachers as never before, while hashtag chats such as #ukyachat and #ukmgchat regularly trend.

“Since JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials,” Jeanette Winterson has observed, “children’s literature has been repositioned as central, not peripheral, shifting what children read, what we write about what children read, and what we read as adults. At last we seem to understand that imagination is ageless.”

It’s true that such books brought children’s fiction to higher prominence in the early 2000s, but they are part of a literature that is continually regenerating itself. And as the generation who grew up on Rowling and Pullman begin to publish their own books, it will only go further.

Yet neither media coverage nor literary prizes have kept pace. Until they do, anyone looking for the richest contemporary literature might be advised to consult the lists for prizes such as the Guardian children’s fiction award and the Carnegie medal instead. Because that is where you will find book after book that stands up to re-reading: the true classics of the future.

From: The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment