by: Katie Gilbert

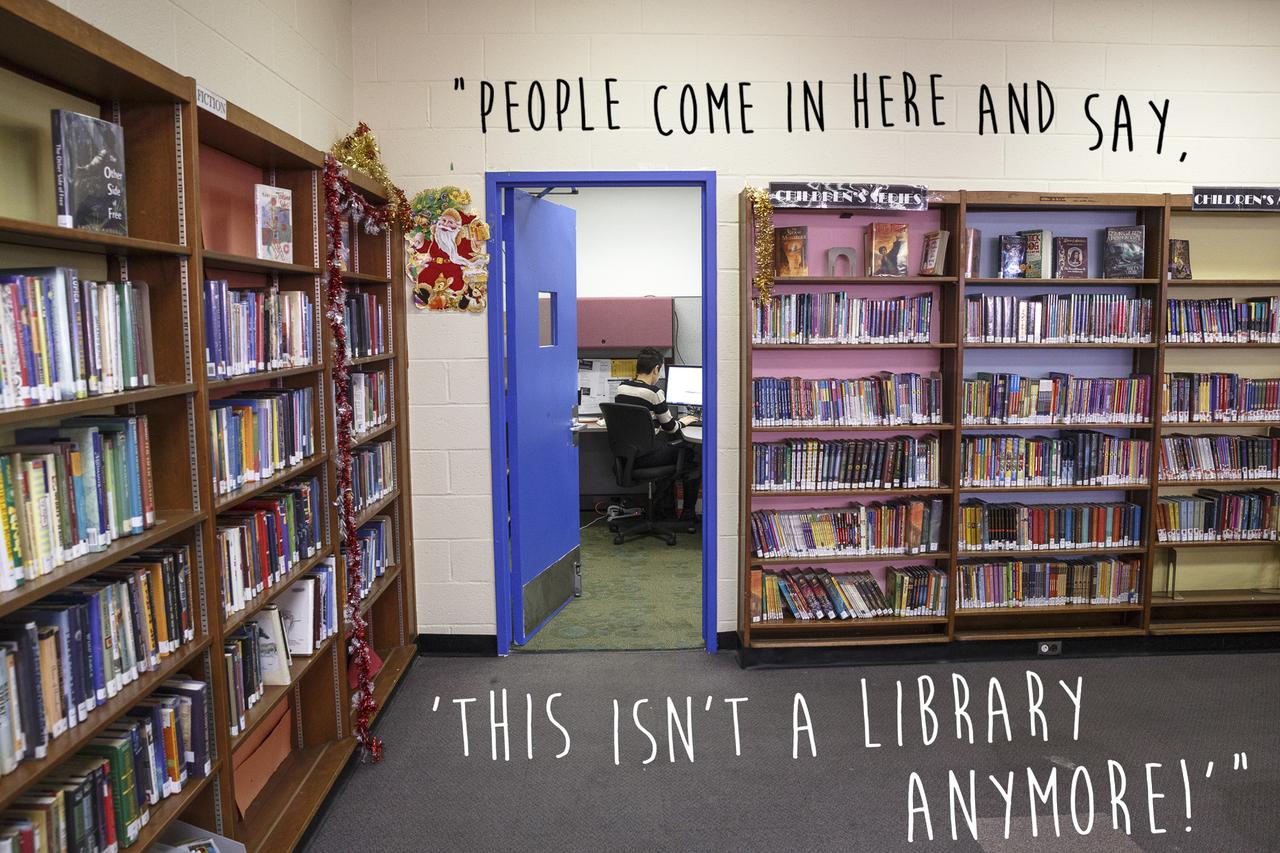

Harlem Shake in a library? Yes!” cries the caption of a YouTube video uploaded

this spring by the regulars of the Queens Library for Teens.

The Harlem Shake at the Queens Library for

Teens.

While watching dozens of

teenagers decked out in parrot masks and Bugs Bunny costumes dancing, jumping

and spinning on rolling chairs across the frame, anyone is likely to wonder:

This was allowed in a library? And upon entering the space where the

clip was filmed, many people do ask: This is a library? Aside from a

few small shelves of test-prep materials, this 3,000-square-foot room holds no

books.

The teen library sits at

the corner of Cornaga Avenue and Beach 20th Street in Far Rockaway. It opened in

a former retail space in 2007 to resolve the mounting complaints from patrons at

the Far Rockaway library branch a block away, who grumbled that the horde of

teens descending on the facility every day after school was just too disruptive.

The teen library is open from two-thirty p.m. to six p.m. Monday through Friday

and admits only twelve- to nineteen-year-olds—not their younger siblings, and

not even their parents.

Kim McNeil Capers, the

teen library’s director, laughs when she says, “Kids don’t come in here to find

books. They come here to find a girlfriend!” That’s only partially true. Capers

is a certified mental health counselor, and before she joined the library she

supervised mental health programs for teens and children. Her face straightens

when she adds: “When they come in here, we’re going to get them the help they

need.”

![]()

It’s a common refrain

among those working in New York’s public libraries these days: Because it’s

increasingly difficult to pin down exactly what kind of help they’re supposed to

offer, librarians have tried to make their mission pliable, and to offer

whatever help people need, in whatever realm it may be. They’re hardly limiting

their offerings to intellectual pursuits.

In fact, no librarians

work at the teen library—youth counselors run the place. And though it’s devoid

of books, the room holds plenty else. After the orange-sherbet walls, the rows

of forty computers are likely to be the first thing you notice. On the opposite

wall, magazine racks house seventy subscriptions, and interspersed with those

are salmon-and-green padded chairs. Upon entering one recent afternoon, a group

of about ten boys immediately pulled them into a circle to facilitate their

noisy Yu-Gi-Oh! trading card game.

When you get to the back

of the room, you’ll come upon the teens’ most prized possession: a $70,000

recording studio, flanked by three editing stations. To one side of that is the

gaming lounge, and to the other side a pool table, which will soon shift roles

to serve as the foundation for a model town with a working model railroad. When

the teens start to stream in, the air swells with friendly yelling, B.O. and the

scent of fast food, but they aren’t chided for shouting or snacking. This is a

place for hanging out.

![]()

However, what the teen

library hopes to offer its young patrons is heftier than that. Far Rockaway

struggles with high unemployment and the social issues common to areas with many

low-income housing projects—problems that have only been compounded by the

neighborhood’s isolated location on a remote barrier beach, not to mention

Hurricane Sandy, which came through in 2012.

The teen library’s daily

and monthly programs are tailored to this vulnerable population, hosting daily

GED prep classes, an annual college fair, health classes, gang awareness

programs, a chess club, CPR training, a Regents Exam prep club, a streaming

radio station via the recording studio, an annual science fair, and scores of

other activities.

The Queens Library for

Teens is a reflection of what New York City’s libraries have come to believe

about themselves: They are in a position to do more than just connect their

patrons to books and content.

* * *

What is a library

for?

That question has never

been as difficult to answer as it is today. Just as the Internet has given way

to identity crises within journalism, publishing, and music, movie and

television distribution, it has also confused what used to be libraries’ central

purpose: providing a singular portal to content for whomever cared to access it.

With the World Wide Web blowing in and demanding recognition as the more

singular portal to the world’s content, libraries’ painstaking cataloguing of

information that is now largely Google-able is looking a bit less critical.

It’s an upheaval that

calls for a more existential grappling than can be addressed by digitizing

library content or installing rows and rows of new computers. Librarians have

had to delve deeper and ask themselves fundamental questions about their role,

such as, what can they offer that the Internet can’t?

“Libraries are

aggressively moving into a range of services that aren’t necessarily related to

book lending,” says Lee Rainie, director of the Pew Research Center’s Internet

Project, a nonprofit research body that has published a series of reports about

how technology is changing expectations of library offerings. “They are pretty

radically rethinking their mission in the world,” he said.

Major cities like New

York may be the most progressive incubators for the trend. Rainie adds, “There’s

clearly something special that has happened in urban libraries, where they are

thinking very seriously about the new services mix that they should offer to

their patrons.”

Library employees from

each of New York City’s three systems—New York Public Library (with branches in

Manhattan, Staten Island and the Bronx), Queens Borough Public Library, and

Brooklyn Public Library—maintain that their institutions are in the midst of a

role reappraisal.

“We’re evolving our

service model,” says Thomas Galante, president and C.E.O. of the Queens Borough

Public Library. He points to shifting budget priorities to illustrate. For

example, when the libraries suffered deep funding slashes in the early 1990s and

again in 2001, Galante and his colleagues delegated cuts based on where they’d

have the least impact on circulation. Library locations with the most in-and-out

book traffic stayed open six days a week, while those with more anemic

circulations only opened their doors two or three.

But by the time

libraries saw funding pull back again in 2008, priorities had reversed. The

system’s directors wanted to ensure that each of its sixty-two branches would

open at least five days a week, so the books budget bore the brunt of the

cutbacks as it was snipped in half.

“We know there are all

sorts of other reasons why people walk through our doors—for programs, for

computer access, for a place to get out of the heat,” Galante says. “We thought

that was more important than having twice as many new books on the shelves.”

Brooklyn Public Library

chief librarian Richard Reyes-Gavilan notes similar changes pervading his

system. “I’d love to say we’ve made this conscious decision to sort of

reevaluate our role in people’s lives, but really all we’re doing is responding

to community needs,” he says. “Our physical spaces are situated across the

borough to deliver informal, nontraditional educational experiences, and that’s

what we’re really moving into.”

![]()

Reyes-Gavilan explains

that when making hiring decisions, “we’re not necessarily asking people anymore,

'Tell us what experience you’ve had with reader advisory or cataloguing.’”

Instead, he asserts, the system’s higher-ups are more apt to value experience in

education or social services.

All three of New York

City’s library systems are in the process of building out new departments and

positions that more readily evoke a social worker’s job description than that of

a traditional librarian. In September, BPL launched its new Outreach Services

Department, which will eventually consist of five full-time staff members tasked

with expanding services for immigrants, senior citizens and prison populations.

In October, NYPL began hiring for the new role of “intake managers,” library

employees who will help patrons sift through the growing number of programs, and

who will maintain a hands-on role after doing so, contacting patrons when, for

example, they miss classes for which they’ve registered. For its part, the

Queens system has six full-time and two part-time case managers—all hired since

2009—who help visitors navigate the murky waters of government programs and

services.

In the decade between

2002 and 2011, the number of programs offered across the city’s 206 branches

jumped twenty-four percent, and the number of attendees at those programs shot

up by forty percent, to 2.3 million, according to a Center for an Urban Future

report.

These changes are making

for an altogether different library experience. Galante says they have

designated quiet rooms recently because “the rest of the library isn’t as

quiet.”

“People tend to think of

the libraries they grew up in,” he adds. “But those are very different than

walking into a public library today.”

* * *

Over the past five

years, Madlyn Schneider has helped transform Mail-A-Book—a library program based

in the Queens Village branch that delivers books and other materials to New

Yorkers unable to leave their homes because of age or disability—from a

straightforward delivery service into the teleconferenced social life of dozens

of Queens’ homebound residents.

Bonnie Sue Pokorny was

just looking for something to read when she first contacted Mail-A-Book in the

early 1990s. At that time, Pokorny, now sixty-eight, had recently been diagnosed

with a rare neurological autoimmune disorder that came on quickly and brought

with it frequent bouts of dizziness, fainting and overheating. She had always

been active and independent; she’d raised three children by herself, worked full

time managing the claims department of an insurance brokerage house in Nassau

County, and ran a large late-summer street festival in Queens for thirteen

years. But when her illness hit, it cost her almost more effort than she could

bear just to sit up. Her doctors told her she’d never work or drive again.

But she had always been

an avid reader, and at least that was something she wouldn’t have to relinquish.

She learned that Mail-A-Book could help with that, and for the majority of the

intervening twenty-three years she’s been bound to her Forest Hills apartment,

it has.

But things started to

change for Pokorny when Schneider took over Mail-A-Book in 2008. Schneider had

previously worked in an administrative role at the library, which required her

to spend hours sitting in boardrooms on conference calls and staring at Polycom

teleconferencing technology in the center of the room. In her new role, she

started to wonder: What else might the library be able to do for the roughly

four hundred socially isolated patrons receiving book deliveries from her staff?

She applied for a small grant from the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation

and used it to purchase teleconferencing equipment. The library system agreed to

foot the monthly bills for an 800 number.

At first, the

Mail-A-Book teleconference chats happened only on Friday mornings, and were

strictly book-related. Mail-A-Book users could call the 800 number to chat with

other patrons about the books they’d read that week. As demand grew, the library

added a Tuesday afternoon session. As New Year’s Eve approached, a woman on one

of the calls complained that she dreaded the holiday for how lonely it made her

feel—a sentiment shared by many on the call. So Schneider convened a telephonic

New Year’s Eve gathering from home that year, and another the next day.

Schneider kept coming up

with new possibilities for the library teleconferences: art lectures from

docents at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art;

collaborating on crossword puzzles via Skype; performances over the phone from

musicians and comedians; emailed newsletters with patrons’ own art, poetry,

recipes and book reviews; and, eventually, occasional in-person lunches in

Queens diners for those Mail-A-Book members who could venture out.

![]()

Over the past few years,

Pokorny’s phone-based social world has ratcheted to a level that might be more

normal for a patron of the teen library—her Mail-A-Book commitments generally

call for her several times a day. “Before, I was always trying to make sure I

had a lot of projects in the house to keep busy, so the four walls weren’t

climbing on me,” she says. “Now I don’t have time for my own projects. There’s

always something going on.”

Pokorny got something

else out of Mail-A-Book she hadn’t expected the program could provide: a new

friend. She was introduced to Margo during a Mail-A-Book teleconference, and

although they never met in person, the two of them were soon calling each other

up three or four times a day. They took online classes together that they’d

learned about through Mail-A-Book, and helped one another with the homework. “We

had the same sense of humor, the same interests,” Pokorny says. “A lot of our

experiences were similar.”

Margo passed away last

December at seventy-seven.

“We became very, very

close,” Pokorny says. “I had Margo in my life for maybe a year and a half before

she died. I consider that year and a half very lucky, because you don’t make

friends when you’re homebound. You might have acquaintances, but Margo and I

were fast friends.”

Today, Pokorny is more

tied up than ever in Mail-A-Book, and at this point, most of the services she

receives from the library have little to do with books.

“With all the activities

in Mail-A-Book,” she says, “I don’t have time to read.”

* * *

The consensus among New

York City library employees about what exactly has happened within their

institutions over the past decade starts to crumble when they acknowledge that

the library is no longer the book-and-reading-centered body it used to be.

What, then, is the

library becoming? QPL’s Galante rejects the suggestion that his libraries are

becoming indistinguishable from social service agencies.

“People come to the

library today to find a new job, learn a skill, take a GED class. These are all

things that someone could dub as social services, but they’re not,” Galante

says. “A public library today has information to improve people’s lives. We are

an enabler; we are a connector. When it comes to social services, a lot of what

we do is help people by referring them to places they can go.”

Sandra Michele Echols,

interim manager for QPL’s adult literacy program, is of another opinion. She’s

in the midst of writing an article about the direction public libraries are

headed, and its working title aptly summarizes where she stands: “I Could Tell

You Stories: Am I a Librarian or a Social Services Manager?”

Echols joined QPL in

2009 as the system’s first case manager, screening and referring library patrons

to nonprofits and government organizations that could help meet their needs. She

says the role of a designated case manager had been made necessary by the

passage of the

E-Government Act of 2002, a federal law that sought to allow

citizens access to a wide range of government information and services via the

Internet. The act was widely hailed as a boon to the working class, who’d now be

less likely to have to miss a day of work for a visit to the DMV. But others,

including Echols, complain that an unintended consequence of the act was that it

put significant pressure on public libraries—particularly in a place like New

York City, where, as

a report from Comptroller John Liu’s office noted in April,

nearly a quarter of households don’t have a computer.

“Now that the

E-Government Act has been passed, it helps the working class do things really

easily, but it alienated the poor and furthered the digital divide,” Echols

says. “And now, social service agencies are telling individuals, ‘Go to your

public library and have them help you print out your child support, or the

application for housing.’ So that’s becoming a real specialty for

librarians.”

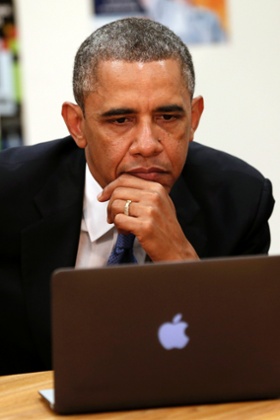

The Far Rockaway branch

brought in a case manager who set up her own office in the library building in

early November. Sharon Anderson, the branch manager since 2008, says she had

become so overwhelmed with requests for help filling out government forms,

assisting with job applications, calling battered women’s shelters, and, in one

case, finding a rape hotline, that it became necessary to situate a case manager

in the building.

Anderson’s branch

doesn’t exactly greet its visitors with the enforced hush most expect of a

library, but it doesn’t shriek with chaos, either. The buzz of activity falls

somewhere in between—it’s the sound of a space being utilized in layers.

Bookshelves line the perimeter of the 6,300-square-foot library, allowing ample

room for about twenty computers (all in use on a recent weekday afternoon); a

set of gleaming white cubicles that house the Workforce1 Career Center, a job

placement service run by the NYC Department of Small Business Services; a kiosk

with information about the branch’s new Google Tablet lending program; and

several tables where dozens of students cluster each afternoon for an

after-school tutoring program funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s 21st

Century Community Learning Centers initiative.

“People walk in here and

say, ‘This isn’t a library anymore!’ Well, you know what’s funny?” Anderson

says, pausing to laugh. “It’s really not!”

She says that sometimes

people complain about the level of activity in the building, but she hasn’t been

surprised to discover that much of her job description requires her to raise her

voice above a whisper.

When Anderson earned her

master’s degree in library science from Queens College in 2004, she presented

her thesis on what she saw to be a blurring line between librarians and social

workers. “I started to see an evolution where librarians were getting away from

sitting at a desk and checking out books,” she says. “I knew I was going to be

taking on more of a social services role.”

![]()

As we talk, a woman in a

red sweater and Iris Apfel glasses approaches Anderson’s desk and, pointing her

cane in the direction of the street, complains that she’s been wrongfully stuck

with a parking ticket. Anderson listens, then explains how the woman can contest

the ticket by mail.

When the woman walks

away, Anderson says she believes the changes in her library have been driven by

“too many social issues and not enough social agencies,” combined with her

institution’s broad mandate and its eagerness to adapt. “Part of our mission is

to help people,” she says. “We’re just responding to the environment, and

continuing to say, ‘Whatever your needs are, we’ll help you.’”

Of course, changes

within libraries aren’t met with blanket acceptance. In a Pew Research Center

survey of Americans’ expectations of libraries in the coming years, respondents

were generally supportive of new technologies, apps and lending programs, but

they weren’t sold on the idea that “libraries should move some printed books and

stacks out of public locations to free up space for tech centers, reading rooms,

meeting rooms, and cultural events.” Thirty-six percent of respondents said

libraries should “definitely not” push books aside for these other types of

programs, while thirty-nine percent answered that “maybe” they should. Only

twenty percent were “definitely” on board with such changes.

Little surprise, then,

that NYPL kicked up such fervent controversy when it announced its plans to

renovate its flagship research library, the lion-guarded Stephen A. Schwarzman

Building on Forty-Second Street. The plans are Pew’s hypothetical made literal:

in order to combine services from the Mid-Manhattan Library and the Science,

Industry and Business Library into the building, books and other research

materials will be shipped to a storage facility in Princeton, N.J., to make way

for not only a new circulating library, but additional computers, group work

spaces, an expanded children’s room with new programming, and the building’s

first-ever teen room.

![]()

“Will Forty-Second

Street remain a serene environment for scholars, serious readers, intellectuals

and book lovers, or will it be converted into a noisy, tumultuous branch

library?” Scott Sherman wondered

in The Nation, in one of a series of articles that criticized the

renovation plans.

John Lundquist, a former

chief librarian of the NYPL’s Asian and Middle Eastern Division, was forced to

retire in 2009, a year after the division was closed. Lundquist is concerned

about the main branch’s renovation plans, but he stresses that he draws a strong

distinction between the mandate of the city’s research libraries and its branch

libraries.

“I feel that the branch

libraries, and public libraries in general, are totally right to go in

directions [in which they assume a] much broader social mandate,” he says. But

the changes shouldn’t extend to research libraries, he says. The relocating of

research collections to make way for other types of library spaces constitutes,

he believes, “the tragedy of the dumbing-down of the research collections of

NYPL.”

* * *

It’s the Monday evening

before Thanksgiving, and the Far Rockaway branch is throwing a party. The tables

that would have otherwise been host to after-school tutoring are pushed out of

the way to make room for a few dozen chairs facing a makeshift stage where

one-man-band Peter J. LaRosa regales the crowd of roughly fifty with big-band

classics.

Behind the chairs where

concertgoers sit, a line of volunteers scoop steamed vegetables, mashed potatoes

and gravy, stuffing, and turkey out of tinfoil pans onto the line of plates

moving past.

Two middle-age women in

the audience, Shirley and Debbie (both declined to share their last names), have

come to the library to see LaRosa, whom they once saw perform at a nursing home.

They marvel that such a noisy event would be held in a library.

“I’m surprised they’d

allow food in here with the books!” Shirley says.

Debbie nods in the

direction of a group of youngsters jump-dancing to a Tony Bennett tune and

chortles. “These kids don’t look like they’ll be looking at books after

this.”

A woman shrouded in long

dark hair, sunglasses, and wine-colored lipstick chimes in, telling me about the

free jewelry classes she took at this library branch the week before. “And it’s

not with the plastic stuff—they give you nice stones,” she says. “And you get to

keep it.” She adds that the library’s programs are good for Far Rockaway. “Thank

goodness they think of this stuff, because there’s not a whole lot else out

here.”

But, she adds—and now

she’s shouting to be heard over a tangle of teenagers wrestling over a cell

phone—she misses having a quiet library where she can just go to read.

So what’s more

important, I ask: A library that excels in the programs, or one that has

mastered the quiet?

“Both,” she says,

without missing a beat. “A library should be both.”

* * *

Katie

Gilbert is a freelance writer based in New York City. She has written

for TheAtlantic.com, Psychology Today, Institutional Investor, Willamette Week,

and others.

from:

Narratively