by: Jessica Leber

When I received the Brooklyn Public Library’s recent email newsletter promoting a new service called BookMatch, I was both delighted and dismayed.

On the one hand, it was a great idea. All I had to do was fill out a short web form letting the librarians know a bit about what I wanted to read and what I liked to read, and one promised to write back with five personalized recommendations tailored to my interests and tastes. On the other, the fact I was so delighted was exactly what was dismaying.

Librarians have been suggesting books to patrons for literally forever, mostly during actual face-to-face conversations. Is this what our algorithm-mediated online bubble worlds have come to, I thought? That I’m so accustomed to Amazon’s recommendation engine telling me books I’ll like, or Netflix’s cloud computers judging the core of my being, or Facebook jiggering with my News Feed to suit its own bottom line, that it is so surprising--so seemingly innovative--that a real human person (a book expert!) who is not my mom or my friend wanted to put thought to what I might like to read? Over email no less?

I wasn’t the only one tickled by this new/not new idea. “August 22. The date BookMatch launched is burned in my mind because we had so many responses come through,” recalls Amy Mikel, the Brooklyn Public Library’s outreach librarian.

It turned out that librarians do not scale well.

In fact, the service, which consists of about 40 branch librarians fulfilling BookMatch requests alongside their regular work, was initially overwhelmed by hundreds of patrons sending in forms on the launch day. It took a few weeks, not one week as originally planned, for staff to move through a backlog of the varied requests. Users ranged from a mom starting an anti-bullying school book club to the person who simply wanted to know, “What’s the next Gone Girl?" says Mikel.

Here’s an example of one of Heath’s suggestions:

Among Others by Jo Walton: There are elements of fantasy, science fiction, and coming of age in this novel about a young Welsh girl who is sent away to boarding school after her twin sister dies in mysterious circumstances. Morwenna believes that her mother, a powerful witch, caused the death of her sister and must be stopped; meanwhile, she struggles to make friends in the unfriendly girls' school and tries to lose herself in every science fiction novel she can get her hands on. (I've included this title as a suggestion not only because it's a cracking good read, but because Morwenna lists and discusses a number of her favorite sci-fi classic titles, so it serves as a kind of reading suggestion list in itself!)The Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) isn’t the first to experiment with online book recommendation systems for patrons--the Seattle Public Library has the similar “Your Next Five” program, for example. What’s noteworthy is that public libraries are choosing to devote their underfunded budgets to such a service at all, especially at a time when many basic library services are becoming more automated. (Librarians are instructed to take no more than an hour on each request; most, Mikel says, average about 30 to 40 minutes. It’s helped that the number of new requests has leveled off to just a few a day since the original promotion).

“A few years ago, there was a lot more concern among the public that libraries are obsolete. I don’t really see that anymore,” says Mikel. In fact, libraries all over the country have been on a quest to innovate. “A service like this is really helping to affirm that idea.”

The human expert versus algorithm debate is as old as computers themselves. It comes up in endless variations. But recommending a novel I’ll spend hours reading and thinking about is a way more personal than suggesting which shoes I might buy. This is why Mikel believes BookMatch touched a nerve. “It’s something we already knew--that there’s a lot in book recommendations that can’t be artificially generated,” she says. “Why you may like a particular book and why someone else likes the same book may be for totally different reasons.”

Clearly, the librarians believe that human tastes and discretion are still relevant, even as automated algorithms are influencing an increasing portion of the media we consume, whether in the form of news, books, music, or movies. But are a book expert’s personalized suggestions really better than what I might get from Amazon, a site that hasn’t employed a human editor for its home page in 14 years? It’s very possible my positive feelings about the BookMatch program are sprung from mere sentimentality.

My experience only scratches the surface of the differences between humans and algorithms, and the strengths and weaknesses of each in helping people to filter the ever-expanding universe of culture available at our fingertips. Most interesting, perhaps, is that it helped me realize that the boundaries between people and machines are actually far more blurry than they’re usually portrayed. Many BookMatch librarians, for example, are using algorithmic analysis and recommendation software, such as a program called NoveList, to start them off on their suggestions. What the librarians are doing is picking queries that match their expertise (in, say, science-fiction or children's books) and adding an extra level of curation. As Mikel puts it, they're looking for clues and trying to really listen to "what I hear this reader is saying." Even the BookMatch emails, like the one Heath sent me, often start from a script that the librarians edit and personalize. "We really want it to sound like that particular librarian, and not just a canned response," says Mikel.

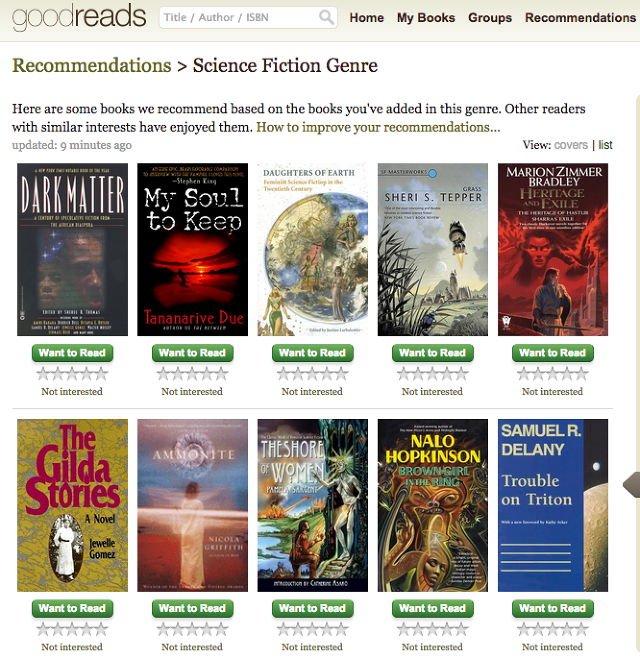

On the other side of the spectrum, Goodreads’ algorithmic recommendations are in reality built upon billions of observations about human activity on the site in an attempt to capture surprising relationships between books that surface only from looking at large-scale user data.

The goal, says Goodreads Vice President of Engineering Brian Percival, is to "give readers a novel and surprising recommendation experience." However, that also takes plenty of tweaking. The software, he explains, knows not to recommend the super obvious--like the same author or series you've just read--and it must also account for things like the "Harry Potter effect," in which hugely popular books that cross a wide audience can confuse the program. It also can work better for certain categories of books, such as topical nonfiction, than for others, like non-English language fiction (just because two French readers choose books written in French, doesn't mean they both like the same kinds of books).

What's also useful is that the platform has non-algorithmic book discovery features that still manage to scale well: Users can ask their Goodreads friends what to read, browse a trove of community-created book lists, and ask the larger Goodreads community of 30 million users for reading suggestions. (When I try the latter, I received six notes from helpful strangers within a day). “A lot of this stuff between machines and people--it all goes hand in hand,” says Goodreads Vice President of Operations Kyusik Chung. “Machines use a lot of people, and people use that information to inform their own recommendations.”

The real difference, then, between the library’s BookMatch service and a site like Amazon or Netflix may be less about the method and more about the motive. One is commercial, the other is not. Both want to recommend books people will like--but the commercial interest is to sell more books and the calculations behind that are not transparent to the user. Librarians, says David Weinberger, the recent co-director of the Harvard Library Innovation Lab, are “unreservedly” on the side of the reader, and often attempt to expand the reader’s interests and stretch his worldview.

“If you’re Amazon, you want to recommend books that people like, so they’ll come back. But if you’ve read Gone Girl, then Amazon is likely to recommend books that are very much like Gone Girl in all the best ways they can find,” Weinberger says. “A librarian is likely also to recommend things very much like Gone Girl, but maybe she’ll also suggest books that are not exactly like Gone Girl and are more of a risk.”

And so, that, in the end may be the ultimate value that libraries serve readers, whether through a limited in scale, human-powered BookMatch or even an automated book recommendation engine that a library decides to write (right now, the Harvard Library Innovation Lab is working to do a version of this by opening up its data to developers who could then build apps).

“What is the next thing that you should read? It’s not simply the thing that will have the lowest barrier to embracing it,” says Weinberger. “One of the great virtues of libraries is that they have the reader’s interests at heart. That doesn’t necessarily mean that all humans trump all algorithms.”

Now, I’ll actually have to read the BPL’s recommendations. The only problem? A year after I’ve moved to Brooklyn, I still haven’t actually gone to pick up my library card. But that’s a whole different challenge libraries face.

from: Fast Co Exist

No comments:

Post a Comment