It's not that hard to

think of something totally original. If you don't worry about it being any good,

it's easy. "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously," was Noam Chomsky's spirited

attempt in his ground-breaking 1957 book on linguistics, Syntactic

Structures. "Hold the newsreader's nose squarely, waiter, or friendly milk

will countermand my trousers," was Stephen Fry's during

an episode of A Bit Of Fry And Laurie. But when novelist

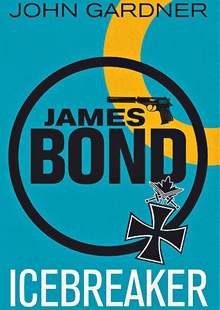

John Gardner used the phrase "opening the throttle at the last moment" in

his 1983 book Icebreaker,

it's unlikely that he sat back and congratulated himself on being the first to

have written it. Innovation wasn't what he was aiming for, after all; he was

just trying to describe someone driving a scooter. But Google Books, that vast indexing project, informs us that

Gardner's was the only book to contain this phrase until another, Vestige Of

Evil by Len Vorster, appeared on Amazon in 2011. A section of the novel, one

of two books self-published online under that name, featured other phrases that

were no longer unique to Icebreaker, such as "the ice and snow were not as raw

and killing as this" and "the slope angling gently downwards to flatten". The

many coincidences were startling, though if it wasn't for the internet, nobody need

ever have known.

In fact, if it wasn't for

the internet, there might never have been a Vestige Of Evil. Vorster (not the

Australian concert pianist of the same name, and most likely a nom de plume)

appears, like millions of others, to have been inspired by the sheer quantity of

online content and the new opportunities for digital self-expression. With

a potential audience of billions, the prospect of contributing can be thrilling;

meanwhile, the moral responsibility we traditionally attach to creative

expression has been downgraded by the sheer ease of copying someone else's work.

When Richard Condon lifted sentences wholesale from Robert

Graves' I, Claudius and quietly stuck them into The

Manchurian Candidate, he did it the good old-fashioned way. Today,

technology covertly assists us: ctrl+C to copy images, prose, code, video and

more, ctrl+V to paste. The consequences of this can range from sly postings of

other people's witticisms on Twitter in pursuit of retweet glory, to

print-on-demand books that are merely duplicates of other books. Driven by

a combination of greed, confusion, ignorance, pressure, laziness and ambition,

an increasing number of people are looking at stuff other people have done and

thinking, "Wow. That's really good. I'll pretend that I did it."

Justin M Damiano, a story

by American comic artist Daniel Clowes, was

published in 2008 as part of a collection of 23 short stories entitled The Book

Of Other People. It told the tale of a film critic experiencing an internal

struggle over whether or not to review a film positively, and it may have

languished in relative obscurity had the storyline and dialogue not been used by

actor-director Shia LaBeouf in a short

film entitled Howard Cantour.com, which

received its online premiere last December. The similarities between the two

were quickly noted, as was the absence of any acknowledgment of Clowes' work; by

effectively pretending it was his own story, LaBeouf had committed what American

judge Richard A Posner describes in his book The Little

Book Of Plagiarism as "the capital intellectual crime". Intellectual,

because there's no law against plagiarism. Sure,

copyright violation is a prosecutable offence, and Clowes' lawyer immediately

pursued LaBeouf's for a response on that score. But copyright eventually

expires, and even if Clowes had been dead for 200 years, LaBeouf would still

have stood accused of plagiarism. It was that moral offence, the act of passing

off someone else's work as your own, that caused a familiar tsunami of offence

to roar across social media channels.

|

| The Justin M Damiano story used by Shia LaBeouf for his short film. Image: (c) Danial Clowes |

"It's a problem for me, it

really is," says Edward Champion, managing editor of an American blog, Reluctant Habits, which has

frequently expressed contempt for plagiarists. He expounds at length on the

subject, relishing his rhetoric. "When you see someone desecrate this wonderful,

noble medium by not being assed to try to find a new form of expression," he

says, "it's basically a writer signalling utter contempt for the reader. The

plagiarist, to me, is the kind of irredeemable hood that would take bad writing

to a ne plus ultra level."

It's an opinion shared by

British thriller writer Jeremy

Duns, whose work in exposing and publicising cases of written theft has

earned him something of a reputation as a plagiarist's scourge. "When I was in

my 20s," he says, "I was one of the editors at a magazine for English-speaking

expats in Belgium, a kind of Time Out wannabe. I found out by pure chance that

our film reviewer had plagiarised all his reviews from IMDb [the Internet Movie Database] for years. But

even though it was verbatim plagiarism, the editor hadn't really wanted to sack

him. I was shocked. If you're really annoyed by something and people say, 'Oh

no, it's not wrong at all', then you get even more annoyed. So I tend to be like

a dog with a bone."

The act of uncovering and

investigating acts of plagiarism is becoming easier by the day. Search engines,

online plagiarism checkers (of varying quality) and the viral publicity

opportunities afforded by social media all play their part. Plagiarism searches

can be compelling, like addictive puzzles where positive results elicit mental

fist-pumps of delight. (It's unlikely that the unwieldy phrase "mental

fist-pumps of delight" will be plagiarised, but I've set up a Google Alert in case.) Still, it's

laborious, unpaid work. "It takes discipline," Champion says. "You have to sit

for hours looking through documents, and it can be a tedious task." The act of

proving plagiarism can also be unnerving, according to Duns, not least because

getting it wrong exposes you to legal action for defamation. "You open yourself

up to a certain amount of abuse," he says. "It's a lot easier to leave it all

alone. And sometimes I do try to leave it alone," he adds. But both men seem

independently driven by their displeasure. "What keeps us going," Champion says,

"is what we're going to discover."

These searches aren't

restricted to words; content-based image retrieval – ie, searching for images

using the image itself – has been crucial in exposing cases of photographic

plagiarism. Nearly every professional photographer has a story about their

copyright being violated, but that violation can also blur into plagiaristic

acts, where photographers simply pretend that other people's work is theirs. Corey Ann, a wedding photographer

based in Ohio, was appalled when she heard of a photographer advertising their

services on Groupon in 2010 using someone else's work, and she became involved

in exposing it. "Afterwards," she says, "people started coming to me when they

found out their work was being used. I needed a place to put it all, to show who

was doing it and who was affected by it." The result was stopstealingphotos.com, which

documents as many cases as Ann has time to publish. Other websites, such as logothief.com, which exposes the

work of designers who have been, shall we say, a little overinspired by others,

fulfil a similar function. "If these things are in a central location that

everyone can see," Ann says, "it has more impact. It draws attention to what's

happening, and hopefully it deters people from doing it."

But while Ann keeps her

fingers crossed, the temptation to use other people's work is growing as the

volume of it expands. We're in new territory, a confusing online landscape that

more than one person I interviewed for this piece described as "difficult". For

millennia we have absorbed information, mentally processed it, stored it,

retrieved it and passed it on in a slightly altered form and context; now, our

unprecedented exposure to that information makes it convenient to take short

cuts. Video and audio mash-ups are commonplace; an artist such as Girl Talk receives widespread praise for

his (carefully credited) plunderphonics. News outlets report the publication of

news in other outlets as news. Code is endlessly nicked and recycled without

anyone really noticing. "There's a lot to take on board about being in the

digital world," says Vicky Beeching, a writer and broadcaster whose doctoral

research focuses on the ethics of online technology. (I took the second half of

that last sentence directly from her

website; rewriting it just seemed unnecessary.) "It comes with a heck of

a lot of issues," she continues, "including how we delineate between our own

ideas and other people's, whether we should be bothered about it."

Monica Gaudio was

bothered about it. Her recipe for a

14th-century apple pie, published on the medieval cookery website

godecookery.com, was copied, tweaked and pasted into Cooks Source, an American

food magazine, in late 2010. Her name was mentioned on the page, and the

incident may have passed as an unremarkable violation of copyright were it not

for the email that Gaudio received from editor Judith Griggs in reply to her

complaint. "Honestly, Monica," she wrote, "the web is considered 'public domain'

and you should be happy we just didn't 'lift' your whole article and put someone

else's name on it! It happens a lot, clearly more than you are aware of,

especially on college campuses and the workplace." By crediting Gaudio, Griggs

may not have plagiarised in the fullest sense, but she was telling her unwitting

contributors to be grateful for this. Gaudio circulated the email, and the

outrage was colossal; Cooks Source was forced to close. "It was really

venomous and vulpine," Champion says. "And people reacted strongly because they

knew there was an underlying power dynamic in play." It was the familiar tale of

the big guy exploiting the little guy.

|

| Rosie Wolfenden MBE is the co-founder of the much-pirated jewellery company Tatty Devine. "When we started, we felt like we were the only people in the world doing what we do. Today you can see everyone else who's doing it.' Photograph: Tattydevine.com |

While bottles of

knocked-off perfume on market stalls raise few hackles, if a market trader

complained that their idea had been ripped off by Calvin Klein, you can

guarantee there'd be an online petition up and running by lunchtime. While this

comes more under the banner of piracy than plagiarism, many big businesses,

including Tesco, M&S, Urban Outfitters and Claire's Accessories, have found

themselves accused of it. Rosie

Wolfenden MBE, co-founder of the much-pirated jewellery company Tatty

Devine, has seen how this predatory behaviour has affected young designers who

are desperate to showcase their wares but simultaneously terrified of doing so.

"It's the number one concern that we hear about," she says. "When we started,

pre-broadband, we felt like we were the only people in the world doing what we

do. But today, if you do a quick search, you can see everyone else who's doing

it. It feels like it's impossible to have an original idea, and designers are

almost taught to be anxious, because they're being advised not to show anyone

their work." The intense pressure to make money or generate new content has

resulted in a kind of frantic laziness and vigorous corner-cutting. "It's not

that weird if a journalist is pushed for time and they take a sentence off

Wikipedia," Duns says, before stopping himself and reasserting his exasperation.

"But LaBeouf… he took that film to Cannes! Just think about that. He must have

had caterers, sound people, light people – who can go through all that and not

at any point think that someone is going to realise?"

|

| Shia LaBeouf has attempted to style himself as a crusading postmodernist in the wake of his plagiarism scandal. But he is no Laurence Sterne or Jonathan Swift. Photograph: Rex |

LaBeouf's motivations are certainly harder to pin down and more

psychologically interesting. Most creative people have a wistful yearning for

self-improvement, an almost draining need to be seen to better themselves.

Posner describes how they experience "belatedness… a feeling that the niche

[they] might have filled has been filled already". But that pressure to matter,

whether real or imagined, seems to be exacerbated by the internet, and by social

media in particular. We feel compelled to say something, urgently, but we have

no idea what to say, so we repurpose, we borrow and, at worst, we

plagiarise.

At its most extreme, it

can become almost pathological, compulsive behaviour. When the 2011 spy novel

Assassin Of Secrets, written under the pen name QR Markham, was discovered

shortly before British publication to be an elaborate patchwork of several other

spy novels (including, again, John Gardner's Icebreaker), its American author Quentin

Rowan admitted he had been preposterously self-destructive. "It's so hard

to explain logically or rationally," he told Jeremy Duns. "I can only compare it

to other kinds of obsession or addictive behaviour like gambling or smoking… I

knew it would destroy me, [but] it did something for me in the moment."

Champion puts it this way: "When you're published, you raise yourself to a position of power. If you feel that you can get away with it, having bamboozled some of the finest minds in the business, what's going to stop you carrying on?"

|

| Phrases from Icebreaker appear in two other books: Assassin of Secrets and Vestige of Evil |

Creative people are constantly chasing new ideas. "I'm sitting in my study, desperately trying to think of original ways of saying things," Duns say. "If someone takes them without acknowledgment, I don't think that it's a clever piece of art. But the sad thing is that it's probably becoming part of our culture."

Whether Duns' fears come

to pass depends largely on the capricious whims of a younger generation. The

evils of plagiarism may be drilled into university students, with threats that

their work will be checked by that all-seeing-eye of academic fraud, turnitin.com. But, as Beeching points out, the

learning process itself is also being radically reshaped, to a point where the

notion of plagiarism is becoming foggier, and not one that's automatically

synonymous with cheating. "Students don't need to store information in their

brains any more," she says. "I recently read someone refer to the internet

as our 'outboard brain', and now it's surely a question of making a difference

in the world by applying that pool of resources."

As I have read and then subsequently written about plagiarism, scribbling down notes as I go, I have almost inevitably been plagued by doubt as to whether I am having my own ideas or merely expressing other people's in a different way. But maybe that's an anxious by-product of my desire to have my own ideas; the plagiarist, meanwhile, nearly always makes a conscious decision to plagiarise, and by doing so is taking what is largely deemed, at least for the moment, to be the easy way out. "Sometimes, in life and in art, you have to make the difficult choice," Champion says. He's been trying to tell me why plagiarism is wrong, but tails off mid-sentence as he struggles to express his strength of feeling. "And that difficult choice," he concludes, almost triumphantly, "is sometimes finding a way to grapple with a difficult expression of an idea using one's heart and one's courage." Later, out of mild curiosity, I tap these words of Champion's into Google Books and press "search". It turns up nothing.

from: Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment